New light from CLOUD on climate change

In a paper published in the journal Nature, the CLOUD experiment at CERN reports on a major advance towards solving a long-standing enigma in climate science: how do aerosol particles form in the atmosphere? It is known that all cloud droplets form on aerosols: tiny solid or liquid particles suspended in the air. However, how these aerosol particles form or “nucleate” from atmospheric trace gases – and which gases are responsible - has remained a mystery.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), aerosol particles and their influence on clouds constitute the biggest uncertainty in assessing human-induced climate change. Understanding how aerosol particles form in the atmosphere is important since in increased concentrations, they cool the planet by reflecting more sunlight and by forming smaller but more numerous cloud droplets. That, in turn, makes clouds more reflective and extends their lifetimes. The poor understanding of these processes is one of the limiting factors of climate projections for the 21st century.

Thanks to CERN expertise in materials, gas systems and ultra-high vacuum technologies, the CLOUD team was able to build a chamber with unprecedented cleanliness. This enabled them to introduce minute amounts of various atmospheric vapours into an initially “pure” atmosphere under carefully controlled conditions, and start unravelling the mystery.

The researchers made two key discoveries. Firstly, they found that minute concentrations of amines can combine with sulphuric acid to form aerosol particles at rates similar to atmospheric observations. Secondly, using a pion beam from the CERN Proton Synchrotron, they found that cosmic radiation has a negligible influence on the formation rates of these particular aerosol particles.

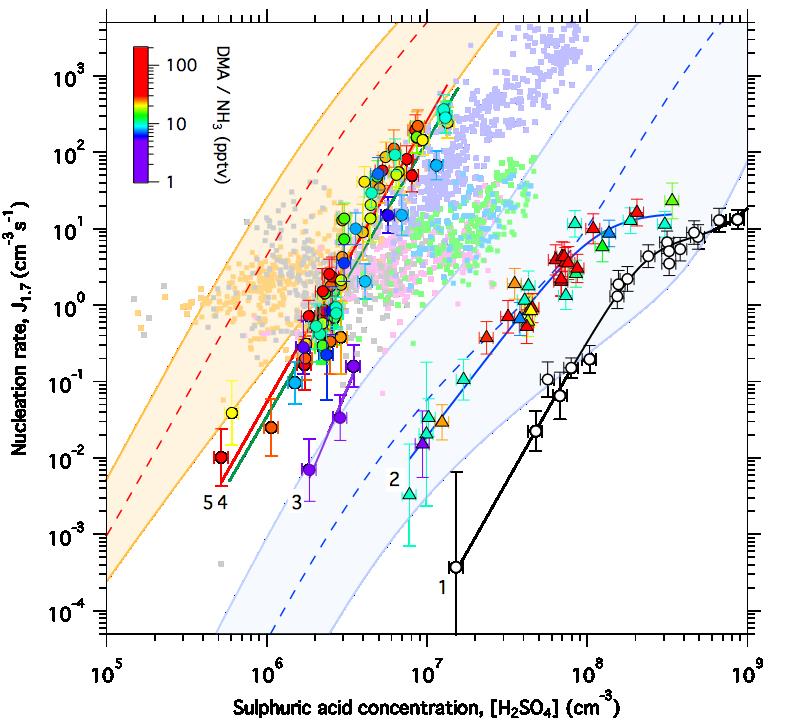

This detailed plot shows the nucleation rate (i.e. the rate at which aerosol particles form) against sulphuric acid concentration. The small coloured squares in the background show atmospheric observations. The CLOUD measurements (large symbols) were obtained with various vapours in the chamber (curve 1: only sulphuric acid and water; curve 2: with ammonia added; curve 3 to 5: with amines added). The dashed lines and coloured bands show the theoretical expectations for ammonia+sulphuric acid (blue) and amine+sulphuric acid (red/orange) nucleation, based on quantum chemical calculations. Only amines reproduced the nucleation rates observed in the atmosphere, while ammonia was a thousand times too small.

Amines are atmospheric vapours closely related to ammonia, arising from human activities such as animal farming and also from natural sources. Amines are responsible for the familiar odours emanating from the decomposition of organic matter that contains proteins. For example, the smell of rotten fish is due to trimethylamine.

Thanks to their unique ultra-clean chamber, the CLOUD scientists have shown for the first time that the extremely low concentrations of amines typically found in the atmosphere (namely a few parts per trillion by volume or pptv) are sufficient to combine with sulphuric acid to form highly stable aerosol particles at rates similar to those observed in the lower atmosphere, as shown on the figure above.

The precise laboratory measurements have allowed the team to develop a fundamental understanding of the nucleation process at a molecular level. The scientists can even reproduce their experimental results using quantum chemical calculations of molecular clustering.

This is the first time an experiment has reproduced the formation rates of atmospheric particles with complete measurements of the participating molecules. So the CLOUD results represent a major advance in our understanding of atmospheric nucleation.

Nobody expected that the formation rate of aerosol particles in the lower atmosphere would be so sensitive to amines. A large fraction of amines arise from human activities, but they have not been considered so far by the IPCC in their climate assessments. The CLOUD experiment has therefore revealed an important new mechanism that could contribute to a presently unaccounted cooling effect.

Moreover, a technique called "amine scrubbing" is likely to become the dominant technology to capture the carbon dioxide emitted by fossil-fuel power plants. Hence, amine emissions are expected to increase in the future and will now need to be considered when assessing the impact of human activities on past and future climate.

The article was originally published in Pauline Gagnon's blog in Quantum Diaries. You can view it here and you can or sign-up on this mailing list to receive e-mail notifications for future articles.