Rosalind McLachlan, a virtual artist exploring CERN

“How often people speak of art and science as though they were two entirely different things, with no interconnection. An artist is emotional, they think, and uses only his intuition; he sees all at once and has no need of reason. A scientist is cold, they think, and uses only his reason; he argues carefully step by step, and needs no imagination. That is all wrong. The true artist is quite rational as well as imaginative and knows what he is doing; if he does not, his art suffers. The true scientist is quite imaginative as well as rational, and sometimes leaps to solutions where reason can follow only slowly; if he does not, his science suffers.” - Isaac Asimov

CERN is a great place for scientists to develop cutting-edge technologies in order to explore the frontiers of human knowledge. Despite Leonard Levinson’s famous quote about history being the “short trudge from Adam to atom” it is hard to imagine how CERN is linked to archaeology and, more specifically, to questions about the past and the meaning of history.

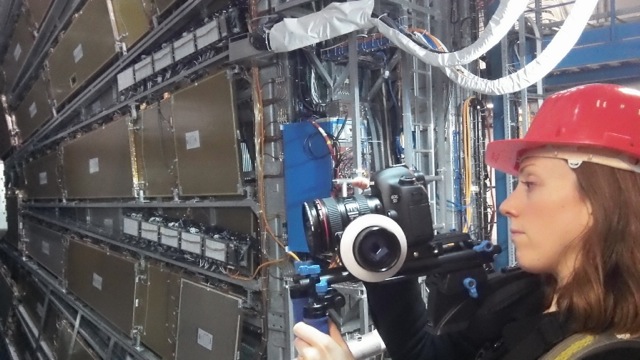

These are some of the questions that inspired Rosalind McLachlan, a British visual artist, who visited CERN earlier this month. Rosalind says: “I try to imagine CERN in the future and look back to it as if it was an archaeological site. If CERN was discovered at some distant point in the future and we had no source of information about it, how would we start dealing with the various artifacts?”. As part of her visit she visited the ALICE, ATLAS and CMS experiments and learned more about CERN’s physics programme. She also had the chance to see ESE’s exhibition of electronics in building 13 and take some pictures in some of the ESE's laboratories where she also met and discussed with students and scientists working on microelectronics. Finally, Rosalind was inspired for her work by the working space of the DT group, next to the entrance of building 166.

Virtual Artist Rosalind McLachlan visited the ATLAS and CMS caverns as part of her visit to CERN.

Rosalind McLachlan studied archaeology at University College London, while at the same time she attended art classes at The Slade School of Fine Art. During her teens she discovered her talent in drawing and, at that time, archaeology seemed like a promising field, as she could combine her artistic skills with her interest in some of the deeper questions about the human origins. As she explains: “Questions like where we come from and why we are here were the type of questions that got me interested in archaeology. These are questions that you can explore as an artist and also as a scientist, like many of the scientists working here at CERN. Those are the questions that I am still exploring through my work”.

Her training as an archaeologist has clearly influenced her work as an artist. Moving from one field to the other seemed quite natural. It was after taking part in a Mayan ceremony that McLachlan decided to become an artist. She spent quite a long time in Central America, living with Maya people and joining them in some of their rituals, visiting with them their cave systems, excavating skeletons and digging in their past. That was the time that McLachlan started feeling quite uncomfortable mining their indigenous history. She explains: “at that point I started wondering how I could actually describe our findings; where were our certainties in these descriptions based? I kept thinking that maybe a different perspective should be adopted and I started investigating their mythological character. That’s how I moved towards art”. She thinks that it is interesting to explore the narratives that we have built in our effort to cope with these questions. In that sense, visiting CERN was like reaching another layer of a different understanding.

McLachlan visited CERN for the first time in November 2012, invited by a friend who has been working with ATLAS. This was when the seed to work on a project related to CERN was planted.

She recalls: “I was doing my own research and study for a long time before coming up with a project. In the beginning, I was trying to get an in-depth understanding of modern physics. It took me like six months of study to realize that as an artist, I don’t have to understand all the equations of physics but rather focus on what the scientific narrative can really tell us about the world and our own place in it”. The effort of physicists to answer the same questions that mankind is dealing with for centuries and the construction of different worldviews is what inspires her.

“Mystery and adventure motivate people to search for answers about their past. If you are a physicist, you want to know about the things you don’t yet understand and I guess it’s the same for archaeologists, historians and those who have a clear eye in the study of the past”. She adds: “I just came back from Arizona where I visited some ancient sites. Each visit makes you wonder and gives you a strange feeling of connecting to the past“. For McLachlan: “the role of art is about making meaning. This has always been important for us as humans in continuing with our daily lives”.

Before traveling to CERN, she was worried that some of her questions might sound too naïve. “Knowing that you will walk in a canteen where you can meet the world’s cleverest mind was in a sense quite daunting”. Fortunately, her fears were dispelled. “I got the strong impression that people want to broaden knowledge. At CERN there is no such thing as a stupid question. Everyone has been wonderful to me and I felt that the best thing about CERN is the people who work here”.

McLachlan adds: “It is not often that you are visiting a place where everyone pursues a higher goal and is dedicated to it”. She was surprised by the feeling of normality that you get while walking on the surface and how different things look when you visit one of the detectors. “It is impressive to see how hard people have worked to build them. The amount of human ingenuity to create such a machine is astonishing”.