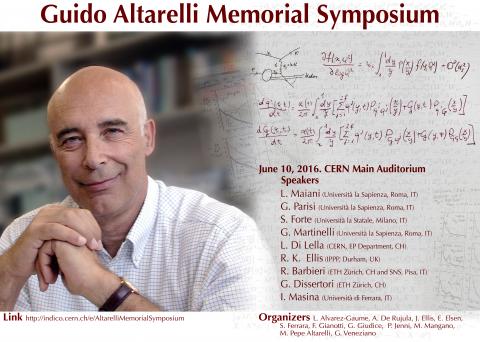

Guido Altarelli Memorial Symposium

The recent Guido Altarelli Memorial Symposium hosted at CERN, honoured the memory of the late Guido Altarelli, a pioneer of the unravelling of the strong interaction and the structure of hadrons, an outstanding communicator of particle physics, and a mentor and strong supporter of junior scientists. Internationally acclaimed for his pioneering research in QCD, weak interactions, precision tests of the Standard Model, neutrino physics and more, he was also universally appreciated for his close interaction with his experimental colleagues.

The event brought together many of his collaborators and friends who gathered to celebrate the life of an exceptional scientist and human.

Guido became a senior staff physicist in the theory division at CERN in 1987; he worked there until 2006, and he served as the theory division leader in 2000–04. In 1992 he joined the newly founded University of Rome 3, where he remained until formal retirement in 2011. He then divided his time between teaching in Rome and conducting research, mostly at CERN. He continued his research up to his last months. Toward the end of his career, he received three prestigious awards: the 2011 Julius Wess Award from Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, the 2012 J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics (shared with Bryan Webber and Torbjörn Sjöstrand) from the American Physical Society, and the 2015 High Energy and Particle Physics Prize from the European Physical Society.

Among Guido’s most important contributions are his papers on octet enhancement of nonleptonic weak interactions in asymptotically free gauge theories. He showed for the first time how the newly born theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) could contribute to solving some of the old mysteries of weak interactions—in this case, the dominance of the DI = 1/2 strangeness-changing processes over the much weaker DI = 3/2 processes. His other important contributions of that period are the first computation of the electroweak corrections to the muon magnetic-moment anomaly, the discovery of a large QCD correction to the naive parton prediction in m+m− production, and above all, the derivations of the Altarelli–Parisi equations. The evolution equations stemmed from an idea of Guido’s to make previously obtained results on scale violations clearer and more exploitable. The paper was written while both authors were in Paris, and Guido liked to remark that it is the most cited high-energy physics French paper.

With the new millennium, Guido started working on a subject he had become fascinated with: the elegance of the tri-bimaximal neutrino mixing. Many of his papers, mostly with Ferruccio Feruglio, are dedicated to the search for the origins of that baffling symmetry.

His scientific success was inseparable from his human qualities. Guido aimed to get a deep understanding of the world, hence his great passion for history, especially that of the many countries he traveled through. His characteristic traits were his great kindness and intellectual honesty, coupled with a rather ironic view of life in general and of himself. His great inquisitiveness and the enjoyment that he derived from learning new things and putting a puzzle together allowed him to summarize subjects in ways that permitted us to take stock of the current state of a field of research and see new directions to pursue. He liked clear, precise formulations that could be understood by all.

Guido was a generous scientist who conceived many of his works in a spirit not only of discovery but also of service to the community. He relished his collaborations in the large particle-physics community. It is difficult to think what the status of the field would be without his contributions.

Giorgio Parisi one of Guido’s close collaborators and friends recalled in his obituary for Gudio:

"It is a very sad event which has brought us together today, since we are here to say a final ‘Goodbye’ to our dear Guido. Our grief is only partially eased by the sight of such a great number of friends who have joined us, some from far away.

Our time on Earth is limited, and Guido’s time was ended too soon. But what is really important is the mark we leave behind. Guido’s legacy is deeply engraved in our understanding of the laws of the Universe and in modern physics.

Guido was a great scientist, gifted with an exceptional talent for physics, as we all know. But he was not a reclusive or selfish scientist, interested only in what personal prestige might be gained from his research. Guido was also a researcher who worked with others within a large community, that of CERN, and in the high-energy particle physics community in general.

Many of Guido’s works, from the most famous to the lesser known, were conceived in a spirit not only of research, but also in a spirit of service to the community to which he belonged. Even his most celebrated work, which we published together, stemmed from one of his ideas, which was to make previously-obtained results on scale violation clearer and more exploitable.

However, those of us who are here today know very well that Guido also left a deep impact on our hearts. For some of us, such as myself, he was a brotherly friend, for others he was a teacher or close colleague, and we all owe something to him.

It’s difficult to think of Guido without remembering his easily-triggered laugh, which was never meant to mock, but was a humorous way of expressing his complicity or his surprise at a new idea. Perhaps his most characteristic traits were his great kindness and intellectual honesty, coupled with a rather ironic view of himself and life in general.

As often happens, his scientific success was inseparable from his human qualities, and did not depend only on his technical capabilities. His great inquisitiveness, the enjoyment he derived from learning new things and putting the pieces of a puzzle together, allowed him to make summaries of topical subjects, which were crucial, not only because they allowed us to take stock of the current state of a field of research, but also because they could indicate new directions to take. He liked clear, precise formulations which could be understood by all. In my case, the collaboration I had with Guido was extremely useful. I did not possess those particular qualities, and so we were complementary.

We saw each other for the last time last July, in Vienna, where we received a prize which we had been awarded jointly. His illness had already begun to progress, even though it was not apparent. We embraced each other, had a long talk, and had dinner twice with Monica, with whom he formed a solid and tightly-bonded couple.

He appeared to be well, and even though I hadn’t seen him for several years, I did not notice anything amiss (not many people knew that he was in bad health). He was the same old Guido, calm and jovial, with whom it was a pleasure to speak. We also talked about his children, and the pride and affection he felt for them were palpable. I’ll never forget his serenity at a time which was so tragic for him, and I do not know if I would be capable of doing the same.

Giorgio Parisi – 6 October 2015"